This week I choose to not be right (and find beauty in a field beyond right and wrong).

Ever been stuck in a toxic relationship rut? I mean really stuck.

Perhaps it was with a spouse, a partner, or your boss or neighbour. An issue arises, they react aggressively, you react just as primitively to their reaction, and so on and on in a spiral of right versus wrong. Soon, you’ve both sunk into a festering quagmire of codependent hurt. You might know better than to descend like this; perhaps you’ve had therapy. But each time the scab’s knocked off the wound, you retaliate like an old lizard. You’re that stuck.

It’s rotten, this quagmire. Blame and shame turn rancid very quickly. And the detritus of old pain gets awfully sticky and suck-holey. So it’s hard to leave, or to shift the energy in a new direction.

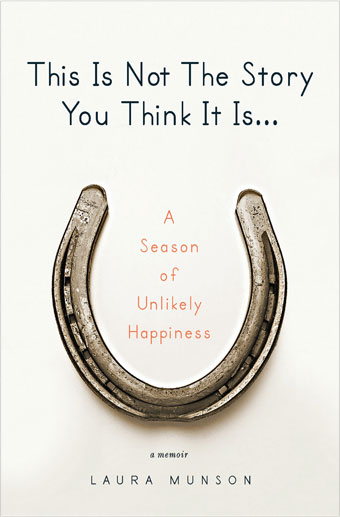

But what if there was another path? Controversially, American writer Laura Munson’s found one and this week she guided me along it. Laura is a publishing phenomenon. Last year she wrote a column in the New York Times‘ Modern Love section about how her husband woke one day to tell her he didn’t love her and was leaving. They were in a rut. Instead of reacting to his reptilian pain, she calmly said, “I don’t buy it”. He was having a crisis that had nothing to do with her. She had to be strong and save the marriage. The column (which also ran in this magazine last year) became the most read item online and has now become a book: This is Not the Story You Think It Is.

Her husband spurted horrible, straight-for-the jugular stuff. Laura bit her tongue. He’d disappear on her and their two kids for days at a time, partying like he was 20, not 40. She held her energy. She was about to lose everything. But chose to be calm and still. And it worked.

At this juncture I’m going to do something I’ve resisted since starting this column: drop in a poignant quote by a long-dead wise person. But it’s my favourite quote and is so wonderfully apt. It’s from the13th Century philosopher Rumi:

“Out beyond the ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing there is a field – I’ll meet you there.”

It hits a spot, doesn’t it? It suggests that not being right (or wrong) is a place we can choose to go to. That it just exists, once we drop knee-jerk judgment, and is entirely accessible. If. We. Just. Choose. It.

Of course we all know to not get attached to other people’s crap. We’ve read the self-help books, downloaded the podcasts. But rarely do we live out such wisdom. Such considered detachment, I think, is the most challenging behaviour in the human repertoire. How did Laura do it? “Every moment I simply committed to end my suffering,” she says. Which was an achievable goal because it was something she could control. Unlike committing to coaxing a wayward husband home. She also cooked and gardened. Which, I find, tends to work for women when they’re going through grand debacles. Nurturing sets a powerful, certain tone for us.

“Plus, I visualised,” she says. When her husband got nasty, she’d see it as the game it was. “Like a ball thrown at me. I could catch it and hurl it back. Or let it drop.”

Chatting to Laura had me reflecting this week on similar grand debacles I’ve faced in my rutted relationship career. I’ve been close to where she was with her husband. And, truth be known, I’m still a little attached (goddamn, I was in the “right”!). How would I do it differently now? I’d commit to ending my suffering, too. Which would mean dropping that “But I’m right” ball. And that “But it’s the principle of the thing” ball. And I’d visualise Rumi’s field, which is where I try to meet most people these days.